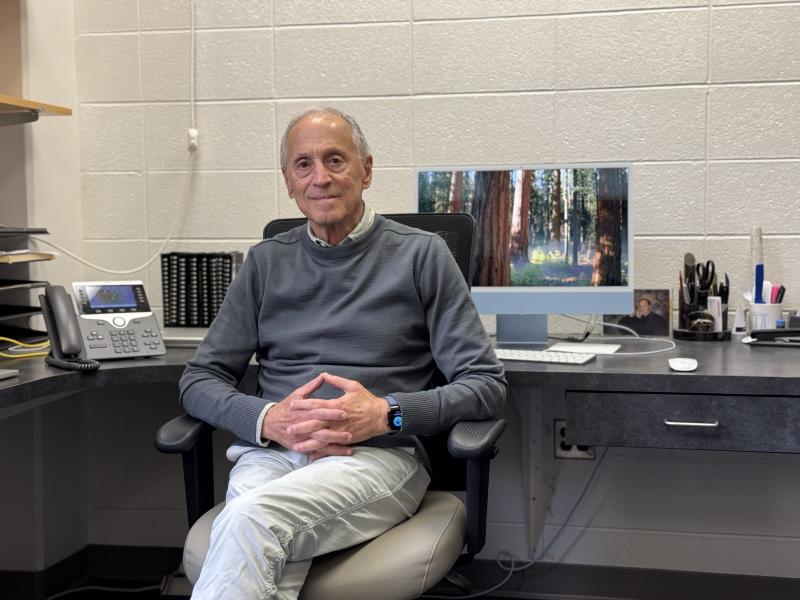

More than four decades ago, Dr. Michael Hershfield arrived at Duke with a passion for understanding purine metabolism and its link to human disease. What followed was a career of extraordinary scientific contribution—one that has quietly transformed the lives of patients with rare immunodeficiencies and severe, treatment-resistant gout. Today, his legacy continues with a generous gift that will support the Duke Department of Medicine (DOM) and the Division of Rheumatology & Immunology in their mission to train and empower the next generation of physician-scientists.

“Mike Hershfield is investing in the future of physician-led investigation in the Duke Department of Medicine. We are deeply appreciative of his generosity and look forward to his continued engagement with young researchers across our department. I hope his gift inspires others to contribute to this mission as we weather current reductions in NIH funding,” said Dr. Kathleen Cooney, chair of the Department of Medicine

Dr. Hershfield’s path began with a deep curiosity about inherited disorders of purine metabolism. Early in his career, he focused on adenosine deaminase (ADA) deficiency, a rare but devastating immune disorder in children, once known to the public through the “bubble boy” narrative. ADA deficiency leads to severe immune deficiency, leaving infants vulnerable to life-threatening infections. At Duke, Hershfield’s lab became a national leader in the diagnosis and biochemical understanding of this disorder. His work contributed to the development and clinical testing at Duke of PEG-ADA (Adagen), which was approved as enzyme replacement therapy for ADA deficiency by the FDA in 1990. Today it remains a lifesaving treatment for newly diagnosed children while a search is made for a transplant donor or a place in a trial of ADA gene therapy.

By far the most common disease of purine metabolism seen by rheumatologists is gout. That painful form of arthritis arises when uric acid, a purine byproduct, accumulates and crystallizes in the joints, causing extreme inflammation. Most patients respond well to allopurinol, a drug that reduces uric acid production. But Dr. Hershfield was concerned by patients he saw in clinic who did not benefit from allopurinol, whose condition worsened over time, causing permanent joint damage and profound impairment. The success with PEG-ADA sparked a bold idea for treating patients with advanced gout.

Dr. Hershfield knew that most animals naturally produce uricase, an enzyme that breaks down uric acid, while humans do not. Building on his lab’s experience with PEG-ADA, he and his collaborators modified uricase using polyethylene glycol (PEG) to increase its stability in the body and allow it to be tolerated by the human immune system. The resulting drug, pegloticase, was licensed in 1998 and approved by the FDA in 2010 under the brand name Krystexxa®. It was the first new class of gout treatment in over 40 years, offering hope for refractory gout patients with no other options.

Developed within Duke’s academic environment, without industry investors or a startup, Krystexxa represents a rare success story in university-based drug development. Dr. Hershfield and his team secured grants, collaborated with industry partners, and carried the therapy through preclinical studies and early clinical trials. Duke retained rights to the invention, and since 2010, royalties from Krystexxa have flowed back to the university, supporting ongoing research within Dr. Hershfield’s lab and the broader DOM.

Royalties to Research

The royalties from Dr. Hershfield’s discovery of pegloticase have long supported strategic research initiatives at Duke, including the purchase of BioRender licenses for faculty, enhancements to Shared Resource Cores, research-focused events such as the DOM’s annual Research Day. Those royalties have also provided bridge funding to help researchers maintain momentum between grants. But in recent years, as the royalties exceeded the needs of his own lab, Dr. Hershfield began to consider a plan for broader impact.

Recognizing the urgent need to support early-career physician-scientists, particularly in a challenging funding climate, he has now assigned a significant portion of the Krystexxa royalties to establish new expendable research funds within the DOM and the Division of Rheumatology and Immunology. These funds, directed at the discretion of department leadership, will support recruitment and start-up packages for young investigators, with an emphasis on laboratory-based research and translational science.

In gratitude, the DOM will name future awards granted through this fund the Michael Hershfield Award for Scientific Discovery, honoring the extraordinary legacy of the physician-scientist who brought Krystexxa from bench to bedside.

The gift is already making an impact. One of the first beneficiaries is Sonali Bracken, MD, PhD, a rheumatologist and translational immunologist who will be joining the faculty in the Division of Rheumatology & Immunology, with significant support from Dr. Hershfield’s gift.

“Michael Hershfield’s contributions to medicine have been life-saving, in the creation of a treatment for adenosine deaminase deficiency in children, and life-changing in the creation of pegloticase for gout,” said Dr. Megan Clowse, chief of the division. “By making a gift to support translational research, he is ensuring that the next generation of physician-scientists has the opportunity to make life-saving and life-changing discoveries.”

Dr. Bracken, a rheumatologist and translational immunologist, specializes in B-cell signaling in lung fibrosis caused by rheumatic conditions. She is positioned to help lead Duke into a new frontier: the use of CAR-T cell therapy for severe autoimmune diseases. Her recruitment is just the beginning of what leadership hopes will become a robust pipeline of young, cross-disciplinary physician-researchers.

Reflecting on his career, Dr. Hershfield often points to the importance of strong mentorship, persistence, and collaborative environments. When he first arrived at Duke, the climate for early-career researchers was markedly different—less structured, but rich in opportunity for those willing to work through the ups and downs of experimental science. Today, the stakes are higher and the path more complex, but his advice remains grounded: “Don’t rush it. Get the training. Find collaborators. Learn to weather the failures. And most importantly, make sure you love the work.”