Compassion is a core value for the Duke University medical community. But how does one go about teaching it? Pose the question to longtime medical educator Diana McNeill, MD, director and a co-founder of the interprofessional Diabetes Clinic at Duke Outpatient Clinic (DOC-DM), and she readily responds, “You can’t teach compassion; you role model it.”

McNeill and the DOC-DM staff role model compassion every day. The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare this year selected the DOC-DM— a community-based practice that treats underserved and often the most medically-complex patients in the Duke system regardless of payer status - as one of eight semi-finalists in the county for its National Compassionate Caregivers of the Year Award. The clinic is a valued community resource in Durham and a primary teaching site for Duke’s Internal Medicine residents and other learners.

The clinic team takes an interprofessional, whole-person approach to care that considers not only medical management but the financial, socioeconomic and psychological barriers that strongly impact diabetes control—issues that may not have not been historically considered in the care of high-risk patient populations from low income brackets. Since its inception, the clinic has come to serve as a best practice model for demonstrating how interdisciplinary care can improve not only patient care, but teamwork and trust among providers—key components of quality and safety.

It Takes a Team

McNeill is a professor in the division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Nutrition, and Associate Dean and inaugural Director of Duke Academy of Health Professions Education & Academic Development (Duke AHEAD). As attending physician at the clinic for 35 years, she is the recipient of the 2022 Duke Medical Alumni Association Distinguished Service Award, which honors alumni whose distinguished careers and unselfish contributions to society have added prestige to Duke University and the School of Medicine.

McNeill and colleagues, Holly Canupp, PharmD, Residency Program Director for the PGY2 Ambulatory Care Pharmacy Residency at Duke University Hospital, Valerie Keck, NP-C, Clinical Director of the DOC-DM, Jan Dillard, LCSW, Elissa Nickolopoulos, LCSW and Allyson Rhinehart, PA, in the division of Endocrinology, started the diabetes clinic in 2018 as a means of addressing the high volume of diabetic patients they were seeing that were not meeting glycemic goals.

They formed a diabetes-focused team that includes physicians-in-training, attending physicians, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, clinical pharmacist practitioner/clinical diabetes educator, registered nurse, certified medical assistant, nutritionist, social workers, and learners from all of these professions.

The whole-person care approach helps facilitate solutions to issues such as uncontrolled diabetes complicated by social determinants of health, ongoing diabetes complications, health literacy, mental health, food or domicile insecurity and medication access, challenges that are typically not addressed or even recognized during a primary care clinic visit.

Patients, for example, often come to the clinic to get their insulin shots once or twice a week when they are supposed to be receiving them on a daily basis but don’t because they cannot afford the medication. The scenario has become a learning opportunity for the staff.

“What this has helped a lot of us do is become more aware, alert, and thoughtful about both the personal and financial costs of diabetes and the impact to patients. Medication access is a huge burden for patients in a low-income bracket,” McNeill says. “When you're trying to manage particularly diabetes, it can be problematic if you don't think about the other issues related to why they're having trouble.”

In addressing the issue of access, the DOC-DM team changed the landscape of GLP-1 prescribed medicines like Ozempic and Jardians to be more in line with the standard of care. Many such medications are covered by Medicare and Medicaid in a variety of ways but historically there has been a bias in not offering these therapies due to the patient's socioeconomic, McNeill says. At the DOC-DM, patients are offered newer standards of diabetes care including glucose sensors and evidence-based diabetes therapies as a matter of course.

Thinking More Broadly

“This clinic not only cares for a patient with diabetes who is truly struggling, but showcases how we can all work together from different perspectives to care for the whole patient,” says Canupp. “Learners are then able to walk away and think more broadly.”

Thinking more broadly about factors like medication access has been an eye-opening experience for first-year IM resident, Kayla Brown, MD. “The clinic is a great example of compassion,” Brown says. “I really admire the way the team thinks and talks about the patient, just using language that is reflective of having empathy and compassion. It's easy to see the disease and not the person when we’re so busy. But throughout the day here, people are checking on how a patient is doing from multiple perspectives, which exemplifies the compassionate care that Dr. McNeil talks about.”

The clinic was developed with numerous learners in mind. Held twice a month on Tuesdays, each clinic begins with a huddle involving a PharmD/CDE, pharmacy students, pharmacy tech, APP, MD, resident/fellow, social worker, nurse, and nutritionist. Representatives from each discipline bring valuable input to the care plan for that day. This allows the team to proactively identify barriers affecting care and complete psychosocial assessments that help uncover and assess previously unidentified issues like cognitive impairment that can impact a patient’s ability to effectively follow a dedicated care plan, Jan Dillard says.

“I have learned so much in particular from our social worker colleagues because they come at this, not from a medical perspective, but from a life perspective,” McNeill says.

“It’s absolutely amazing the unique perspectives that are brought forth,” says Cannup. “You are able to look at the care of the patient as a whole through the eyes of the patient, the clinical social worker, the clinical pharmacist and the medical provider. With this unique lens, we are meeting patients where they are.”

The huddle also serves as an educational opportunity for the different disciplines, and encourages thoughtful collaboration about medical and psychological concerns and various resources available in the community to help patients, lessons not typically taught to medical students. Through the huddling process, the team learns about the scopes and training of the individual professions represented within the team.

The emphasize on whole person care and huddling allows the team to achieve a greater level of care. DOC-DM data shows that taking care of patients with medical and social inequities as well as diabetes complications as a team can have positive outcomes for the patients and team. Hgb A1C, a measure of diabetes control, has improved for clinic patients on average from 9.9% to 8.7%, a clinically significant change, McNeill notes. Team members also report increased competence in caring for diabetic patients and better understanding of the resources available to support them.

“The team huddle is one of the coolest parts about the clinic for me is because it's this whole group of caretakers in one place talking about the patients,” Brown adds. “Normally, we see the same patients, but we don't always get to talk about them and get on the same page. It’s very helpful to hear different perspectives while we all work together to help them.”

Using chart reviews as a foundation, the team develops a plan of care for each patient that builds on the individual expertise of each contributor. The plan of care is then shared with the primary resident provider who also becomes a member of the therapeutic team. There are opportunities for shared visits as well where residents sit in on social work or pharmacy teaching sessions.

“The fact that we take the time to do thorough chart reviews helps us to understand the root cause the barriers our patients experience,” Keck points out. “Compassion motivates us to find solutions to these barriers. We truly find the magic in making a way for our patients. The DM clinic often becomes a highlight of our week giving us joy in the service we provide.”

Additionally, the clinic staff has been able to influence the practice of residents and fellows as they later go on to manage patients. Several have expressed practice changes as a result of attending the interdisciplinary diabetes clinic, Keck adds.

“Every day, the members of this team demonstrate compassionate care for their patients and each other,” McNeill says. “The privilege of having such a team help in the management of diabetes demonstrates to our community and to our patients that team-based care supports all of us. Our DOC-DM team works every day from a health equity position and we all will be better providers and people as a result.”

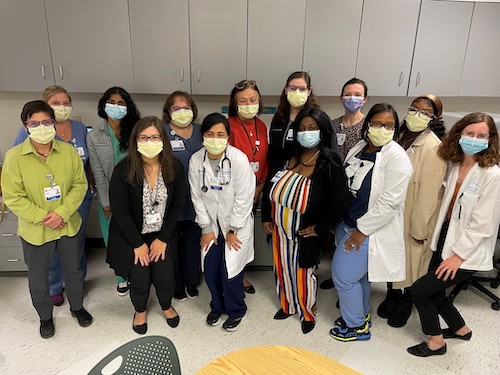

Main photo caption: The DOC-DM interprofessional team huddle serves as a learning experience, offering different perspectives from group members while everyone works together to help a medically-complex patient population.

Photo courtesy of Daniella Zipkin, MD