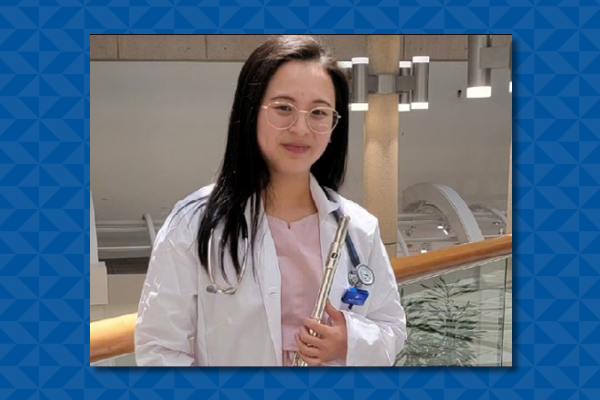

When Senior Resident Kate E. Lee, MD, MS, picked up a flute for the first time in third grade, she never imagined that one day as a physician she would use it as a therapeutic tool to soothe critically-ill ICU patients waiting for heart transplants.

In her recent Senior Associate Resident (SAR) Noon Conference presentation, “Music for Healing,” Dr. Lee’s out-of-the-box topic resonated with all those in attendance—along with each bright note she coaxed from her flute.

“I play music but I don’t think music therapy research is something that comes up often in our rounds in the hospital,” said Dr. Lee, her nimble fingers dancing over the keys in a blur as she warmed up to perform. “The hospital can be a very difficult place, stark and sterile, but when you are able to bring a little piece of your outside life and share that with patients and staff, it makes for a very unique, whimsical bonding experience. I’ve had some of my best patient-doctor interactions from that.”

Dr. Lee brings her little piece of outside life to work most days in a little black case lined in midnight blue velvet. Over the spring and summer, she took it on long calls and night shifts in the cardiac ICUs at Duke and the Durham VA Medical Center.

When she played Gabriel Fauré’s “Sicilienne” for one heart transplant recipient, he told her the piece made him think of his long, agonizing wait for a new heart and the uncertainty involved. It has been experiences like this, Dr. Lee said, that have made her realize that music contributes to healing in an adjunctive way to her medical care, and fortifies bonds with patients. It even generates bonds with strangers.

After one performance at the VA, a veteran came up to Dr. Lee in tears to tell her how touched he was and recorded a snippet for his wife, who used to play flute until she was injured.

“Music can be psychologically and physiologically beneficial, possibly more beneficial than we realize or has been studied,” she said. “Bringing a piece of outside life into the hospital is a wonderful feeling. Patients enjoy that sense of simultaneous oddity and normalcy. Interdisciplinary staff appreciate it, too, and it generates fun and unique experiences to make a regular workday different.”

“Kate’s talk emphasized for all of us that our residents are incredibly multi-faceted individuals,” said Duke Internal Medicine Residency Program Director Dr. Aimee Zaas. “It is always incredible to learn about them as people and reinforces us taking time to get to know about our patients as well.”

Music Therapy

Music therapy has been shown to have some benefits for patients experiencing anxiety and depression in a number of settings such as cardiology, pulmonary and critical care medicine, oncology, psychiatry and neurology, Lee pointed out, with the caveat that these studies generated low quality evidence due to the impossibility of blinding.

Additionally, a 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis of five studies including 209 patients with Parkinson disease showed improvement in various gait parameters with the intervention of rhythmic auditory stimulation, a type of music therapy. There are similar findings for gait parameters in multiple sclerosis.

Music has been a touchstone for much of Dr. Lee’s life. A native of South Korea, she immigrated at age six with her mother, a graduate student in education at the time. They were later joined by her father, an industrial scientist, and settled in Baltimore, Maryland where Dr. Lee began flute lessons in third grade. Her teachers early on recognized her talents and strongly encouraged her to continue studying music throughout her formative years.

On the day Dr. Lee graduated from fifth-grade, her teacher was so impressed by the little girl that she announced she was putting some of her retirement funds into a scholarship for Dr. Lee. Her parents later signed her up for private lessons with a professional flutist who had a track record for preparing kids for All State Band and the Maryland Classic Youth Orchestra (MCYO).

Blossoming

When Dr. Lee tested into an international baccalaureate magnet school, she blossomed as a MCYO member, and was exposed to opportunities that thrilled her. She played the flute solos during one performance at Carnegie Hall and began competing. One win landed her a solo at the Kennedy Center. From there, it was on to Harvard University then Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Dr. Lee told her audience that she has learned a great deal as a flutist that is applicable to medicine, such as a love for the process and what endures from it, not just the results. She draws inspiration from observing the skills of other people, which prompts her to think about how she can improve her art and overcome weaknesses. It also taught her to appreciate her own uniqueness and embrace her strengths.

Chief Resident Dr. Omar Martinez-Uribe has worked with Dr. Lee since she was an intern. He has always been impressed by her dedication—not just to medicine but also to honing her flute skills.

“Her SAR talk was a great blend of her talents,” he said. “The room was not only very interested in the music and her performance but also in the data she presented and how it might impact our patients. Overall, it was a great opportunity to learn about how music can play a role in medicine and to experience several musical pieces performed live."

Dr. Lee is currently applying for a gastroenterology fellowship and hopes to continue playing for her patients throughout her career.

“Perhaps I'll play for patients pre-endoscopy if they wish as there’s some literature on pre-procedural anxiety and music interventions,” she said. “Perhaps I’ll study music therapy in GI. There are lots of options.”

Dr. Lee's Noon Conference Performance

Performed by Dr. Kate E. Lee, MD MS

Cathartic Poetry

Dr. Martinez-Uribe was particularly moved by a heartfelt poem also shared by Dr. Lee, who sometimes writes as a cathartic experience. It was a poem she wrote during residency as a meditation on her first death exam.

“I remember it very well,” she said. “It’s traumatizing and the first one is also awkward. The death exam has components that I outline in my poem. When I lifted the patient’s eyelid to look at the pupil, I didn’t realize it would be so large. It was pretty frightening.”

Read Dr. Lee’s poem “Death Exam”