All was quiet at 4 a.m. in the Duke University Medical Center Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU) as trainees Connor Craig, MD, (PGY-3), Emory Buck, MD, (PGY 3) and aspiring cardiologist Mark Brahier, MD, an intern, routinely went about their duties—until Craig noticed something.

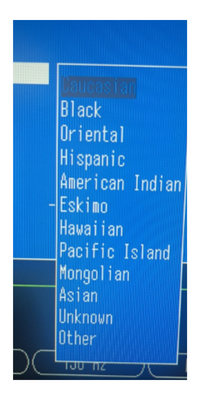

“Does that really say Oriental?” he asked incredulously, pointing to the race description on the EGK printout on the table in front of him.

Brahier powered up the EKG machine on the floor. The three colleagues were shocked to find not only Oriental as a racial choice but American Indian, Mongolian, Hawaiian, Eskimo, and Pacific Islander. Brahier quickly reported their observation via the hospital’s safety reporting system.

Less than 48 hours later, Lisa Pickett, MD, Duke Medical Center chief medical officer, personally stopped by the CICU to look at the EKG machines and presented the issue to the heart leadership team, Jill Engel, DNP, ACNP, vice president, Heart and Vascular Service Line, Duke University Health System, and Manesh Patel, MD, chief of the division of Cardiology. They coordinated to remove the race identifier across the service line of EKG machines.

“This shows the value of people at the very frontline raising safety and diversity issues,” Pickett says. “We encourage reporting, and we are listening.” The interns and residents are a key set of people who bring a different view and allow us to see things that we need to fix. Our diversity and equity training gives us that lens to know when things should be changed. We are more likely to see those problems that we wouldn’t have seen before.”

Clearly, the language was troubling for its misrepresentation of race and ethnicity in the options, an unfortunate remnant of the past, Brahier points out, but equally important is the question of whether race and ethnicity is a clinically meaningful identifier in EKG interpretation.

“As an aspiring cardiologist, I am fascinated by the objectivity of an EKG,” he says. “A simple literature search will show you that the topic of race/ethnicity in EKG interpretation is understudied in most populations. Broadly speaking, there is not compelling evidence that a patient's self-identified race/ethnicity should influence EKG interpretation. An opportunity to eliminate unconscious bias in EKG interpretation is a win for patients. I'm grateful that the Heart Leadership expeditiously reviewed this query and approved eliminating the identifier from routine practice.”

“We are really appreciative of Mark Brahier bringing this issue forward to us, as race/ethnicity does not add clinically meaningful information to the reading of the ECG,” says Manesh Patel, MD, chief of the division of Cardiology. “It's important to recognize that we want our medical information to be accurate, but also not cause or introduce any bias. Age, sex, and weight are generally the indicators that help interpret the ECG.”

Brahier’s action further highlights that work toward improving health equity and reducing bias has to be part of everything we do in health care, with constant, daily evaluation of the status quo in daily work, notes Joel Boggan, MD, MPH, associate program director, Internal Medicine Residency Program.

“In this case, it is not only the fact that Mark has highlighted that there is no value to listing race on the ECG, but in addition the race designations listed are (at best) archaic and (at worst) derogatory,” says Jason N. Katz MD, MHS, director of Cardiovascular Critical Care for Duke University Health System. “Having a fresher set of eyes from our trainees can help us to identify these issues, not only with ECGs but also in the way we deliver care. This is why I love working with bright and inquisitive APPs, students, residents, and fellows. They challenge us to evolve!”

Feature photo: Mark Brahier, MD, at work in the CICU