Health care providers play a crucial role in medical advocacy, and the Duke Department of Medicine is meeting a need for these physicians’ voices by expanding the scope of medical advocacy training to include fellows as well as residents.

An inaugural cohort of fellows, led by Caroline Sloan, MD, began their advocacy work on Thursday, August 17 with the kickoff of the new Fellows Advocacy Curriculum (FAC), an elective track for subspecialty Medicine fellows with an interest in health policy and advocacy. The FAC is designed to prepare physicians to advocate for social, economic, educational and political changes that address human suffering and well-being.

The FAC is an extension of the Duke Internal Medicine Residency Program’s Advocacy in Clinical Leadership Track (ACLT), an elective course of study for second and third-year internal medicine residents interested in health policy. ACLT residents in the spring were credited with playing a role in moving legislation forward that expanded Medicaid in North Carolina, an important milestone for hospitals and patient advocates across the state.

Medical Advocacy Matters

“It's important for physicians to be connected to the system in which they practice and feel empowered to have an impact on improving that system,” said Daniella Zipkin, MD, ACLT faculty director and DOM associate vice chair of Culture, Engagement, and Community. “It also connects doctors in training to the meaning and purpose behind their work at a time where the clinical rigor and pace is astronomical. So, at a very clinically intensive time they can take a breath and be removed from the pace of clinical work to think about and strategize around the systems of care that make their patients’ lives more difficult. It’s a way to take action on the things that are frustrating rather than just let them be frustrating.”

The ACLT experience for Sloan illuminated how powerful advocacy can be. “Learning about advocacy in its many forms can help doctors feel empowered to make change. Once you go to the state capitol or to DC and you speak with staffers or legislators, you realize that you actually have a pretty important voice,” she said. “People listen to you as a doctor. That’s very powerful.”

Sloan will work with the fellows to develop and present their individual advocacy platforms to federal legislators in collaboration with Duke Government Relations. Throughout the year, they will have an opportunity to engage in six half-day didactic sessions and at the completion of the program participate in a two-day trip to Washington, D.C.

The didactic curriculum she has developed provides a broad overview of health policy in the U.S. with themes like the structure of government, healthcare payment models, and the impact of government policies on the physician workforce and their patients. Each fellow is assigned a faculty mentor to provide guidance in selecting a policy issue that is most relevant to their subspecialty and the patients they serve and to assist in making relevant professional contacts.

What Does Physician Advocacy Look Like?

From the physicians’ standpoint, advocacy can take a lot of forms, including direct communication with legislators and staffers or executive branch advocacy involving stakeholders such as the FDA or Health and Human Services. Writing opinion editorial pieces and conducting social media campaigns are also impactful ways for physicians on an individual basis to get involved with issues they care about, Sloan said.

“One thing I've learned since joining the faculty is that you can be a powerful advocate as a researcher as well. If your research is policy-relevant, then you may be asked to advise legislators and their staffers, or certain portions of the executive branch,” Sloan added. “That’s another way that clinicians and researchers can be involved in advocacy.”

For cardiology fellow Nkiru Osude, MD, the FAC curriculum represents an opportunity to harness her skills, seven years of training and passion for decreasing cardiovascular disease burden in communities, into a learning experience that will support her desire to work in the health policy arena.

“I’m interested in being able to obtain as many tools as I can while I'm in fellowship,” said Osude, an experienced health advocate and graduate of the University of Missouri School of Medicine. “Advocacy is very important for physicians. No one knows the health care system more than we do, and there are a lot of people making decisions on behalf of our patients and on behalf of us. So, advocacy is really important for us to have a seat at the table and give our input about what is important for our patients, for our cohort, our physicians, and for other providers as well. Every physician needs to be a part of advocacy in some shape or form.”

Training the Next Generation of Medical Advocates

Zipkin began working advocacy training into the Duke Medicine curriculum in 2012 with the ambulatory care in leadership track. Residents have shown a consistently strong interest in the program since then.

After joining Duke’s faculty, Sloan, participated in the Leadership in Health Policy program (LEAHP), a professional advocacy training program led by the Society of General Internal Medicine. Through this program, she connected to and learned from a national network of general internists who lead advocacy efforts locally and nationally. Sloan developed the FAC to teach fellows the skills she learned during her training and to expand the next generation of physician advocates.

“Medical advocacy is an important part of a physician’s skillset,” said Gregg Robbins-Welty, MD, a Medicine-Psychiatry resident who is active in ACLT and part of the recent drive to advocate for Medicaid expansion. “Doctors are also uniquely positioned to identify gaps in healthcare delivery, share insights from their clinical experience, and to bring attention to challenges their patients face. Interacting with representatives allows for a platform to amplify patient voices, address issues, and highlight the impact of policies on patient outcomes.”

Like Robbins-Welty, fellow medicine-psychiatry resident Ryan D Slauer, MD, came to deeply appreciate the skill of compromise that he honed during his advocacy work.

“When working with people who have different values and priorities, it can be challenging to both argue for your own values while making space for others' agendas,” he said. “Ultimately, though, this is what it means to live in a diverse world and to get along with people who are different than us! But we're the only ones who can speak about our experiences and those of our patients, so we hurt both us and them if we don't advocate.”

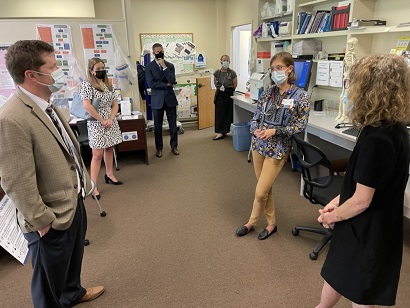

Feature photo: The inaugural Fellows Advocacy Curriculum cohort began work last week. From left to right (back row): Drs. Sabrina Layne, Lisa Pickett, Diamone Gathers, and Anna Laughman. Front from left to right are Drs. Caroline Sloan and Lisa Criscione-Schreiber.