By Mary-Russell Roberson

At the end of April, Duke medical student Godefroy Chery, MHS, found himself behind the podium at the annual meeting of the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation in Washington, DC. “I was a bit nervous,” he says. “You’re talking to people you read about and who have been writing the rules.”

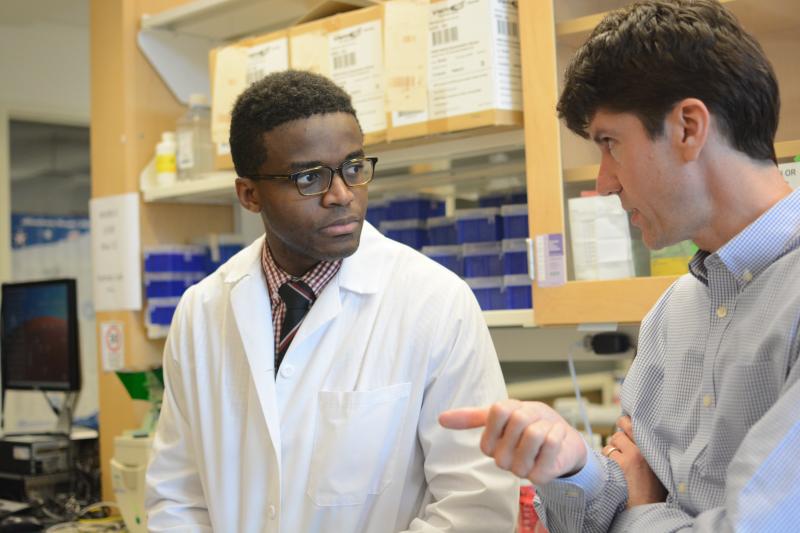

But Chery was ready for his moment in the spotlight, thanks in large part to the mentorship he’s received from Scott Palmer, MD, MHS, professor of medicine (Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine), Laurie Snyder, MD, MHS, associate professor of medicine (Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine), and others in Palmer’s lab.

“It was a pretty big deal,” Dr. Palmer says, of Chery’s presentation. “He did a really nice job. People were interested in the data and very impressed that as a medical student he was able to get up and present it.”

In his talk, Chery summarized the results of a two-year research project in which he analyzed a set of data from lung transplant patients, looking for clues to help predict outcome. The dataset included thousands of patients who’ve had lung transplants at Duke in the past 20 years.

Specifically, he was looking at mismatches in human leukocyte antigens (HLA) between those donating and those receiving lungs. HLA are proteins on the surface of white blood cells that can be used as indicators of immunologic compatibility.

HLA mismatch is known to reduce survival in both kidney and heart transplantation, but it has been difficult to describe the effect of HLA mismatch in lung transplant because there are so many other variables, including the initial quality of the organs. “Lungs are a lot more fragile and they’ve been exposed to a lot of bugs,” Chery says. “My work has been trying to understand if I control for those variables, how much does HLA mismatch matter?”

The strength of Chery’s study was the size and quality of the dataset. He merged long-term data kept at Duke with data on those patients archived at the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). The dataset—both large and longitudinal—allowed him to use statistical strategies to answer more precise questions than had previously been possible.

Bottom line? “Mismatch matters in lung transplant,” Chery says. He found that the total number of mismatches—which can range from 0 to 6—is important, and that mismatches at a particular attachment point—called the DR locus—are especially important.

He is currently writing up his results for publication in one or more transplant journals.

Chery’s work in Palmer’s lab was supported by Duke’s CTSA Scholarship for Pre-Doctoral Students (TL1). Each year, several medical students receive funding through this program, which allows them to spend two years following their second year of medical school doing clinical research in the lab of a senior researcher. After completing one more year of medical school, these students will have earned not only a MD degree, but also a master of health sciences (MHS) in clinical research.

The combination of mentorship, classwork in statistics and clinical research, and hand-on research allows students to make great strides during their two-year experience.

“Chery came in with very little experience doing clinical research and he grew a lot in terms of understanding the research,” Palmer says. “That was rewarding for me to see.”

Palmer did a year of research himself when he was a medical student at Duke, working in the lab of David Pisetsky, MD, PhD, professor of medicine (Rheumatology and Immunology). “The way I approach mentoring,” Palmer says, “is to take what I got out of that experience and try to give it back to students.” He says in Piesetsky’s lab, he learned to think critically and began to see himself as a physician investigator.

Palmer is quick to point out that he was not Chery’s only mentor. “He got mentorship not just from me but everyone else in the lab,” Palmer says. “He was able to get different things from different people.”

Chery also brought his own strengths to the team. “He was a good fit,” Palmer says. “He’s incredibly smart, bright, and hard working, and he’s brought a lot of enthusiasm and a really neat set of life experiences.”

Chery grew up in Haiti, went to high school in Florida, and earned his undergraduate degree from Johns Hopkins.

As a boy, he wasn’t set on becoming a doctor. “My parents were nurses in Haiti so I think that’s where my desire to pursue a field of medicine stems from, but I don’t know if becoming a physician was my ultimate goal,” he says. “Growing up, I had other priorities. In Haiti, you have dreams but at the end of the day, you have to get to the next day.”

Now, on the cusp of becoming a physician, he dreams of a future that includes doing more immunology research. “Immunology is dear to my heart,” he says. “I hope to do more research in the future with the goal of advancing the field. With immunology, you hold the key to solving a lot of diseases."

Medical students interested in research opportunities and internal medicine residency, should check out resources in the Department of Medicine.