When hospitalist Dr. Neil Stafford, began working with undergraduate engineering students, his goal was straightforward: improve how point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is taught to beginners.

What emerged instead was a deeply interdisciplinary collaboration — linking engineering, physician assistant (PA) education, and clinical medicine — that highlights the growing role and need for simulation in medical education.

Stafford has served for several years as a “client” in Duke’s nationally recognized freshman engineering design course, EGR101, where students partner with real-world clients to design solutions for unmet needs. For Stafford, it provided a pathway to bring challenges from the clinical learning environment directly into the engineering classroom.

POCUS: A Powerful Tool

“POCUS is an incredibly powerful tool, but it’s hard to learn,” said Stafford, referring to portable point-of-care ultrasound devices used in the diagnostic process and for bedside medical procedures, distinct from formal ultrasound evaluation in radiology. “Students need ways to practice safely before they’re scanning real patients.”

A year ago, Stafford collaborated with engineering and PA students to create a 3D model showing how the heart is oriented in the chest. During that project, PA students proposed a next step: developing a cardiac ultrasound phantom — a physical simulator that behaves like human tissue when scanned.

During the following fall semester, a new group of four PA students — peer educators who lead POCUS training for their classmates — joined Stafford to formally propose the project to EGR101. The result was a collaborative team of PA students, engineering undergraduates from Duke’s Pratt School of Engineering, with Stafford serving as clinical mentor.

“Our unmet need was simple,” Stafford said.

Cardiac ultrasound is complicated so a physical simulator would make early learning much easier," said hospitalist Dr. Pahresah Roomiany, associate program director for education at Duke Regional who teaches many PA courses. She, too, has used 3d printing to develop more robust POCUS teaching, as learners have difficulty with orientation of the ultrasound probe and how organs are situated in the body.

Simulation Imaging

“Simulation in imaging education is very important since learning is hands on. It takes practice to understand how what one puts the ultrasound probe on translates to what you see on the screen,” she said. “The best way to do this is to be able to see what you are imaging above the skin and below — this is where the phantom becomes so important. This venture is so exciting because it paired medical knowledge and need expressed by medical educators from the PA school and SOM with the expertise of the engineering students.”

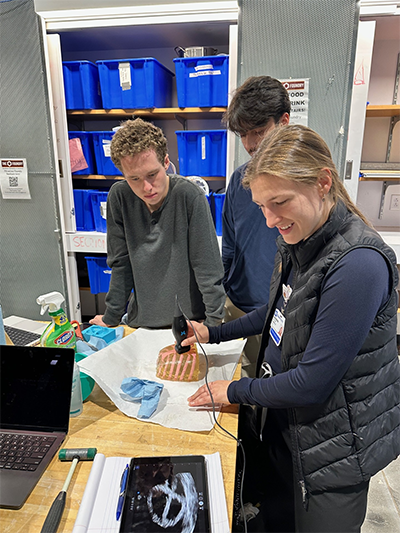

Throughout the semester, the PA students worked closely with the engineering team, explaining the challenges novices face when learning ultrasound — difficulty visualizing anatomy, understanding probe position, and interpreting images. Engineers translated that feedback into prototypes, refining the design through repeated meetings.

“This project’s success is due in large part to an incredible team of freshman engineering students,” said Stafford.

To better understand the learning environment, the engineering students went to the PA school’s ultrasound lab, where they observed PA students practicing scans on one another.

“They needed to see how ultrasound education actually works,” Stafford said. “That shaped how the phantom would fit into real teaching sessions.”

By semester’s end, the team delivered a two-part solution. First, they created a physical cardiac phantom made from clear gel-like materials and 3D-printed components that mimic human tissue. Inside the model is a heart surrounded by a rib cage, allowing learners to see how anatomy and rib positioning affect ultrasound images.

Ideal for Early Learners

“This is ideal for early learners,” Stafford said. “They can see how the probe interacts with the chest and understand the anatomy in three dimensions.”

Second, the team produced reusable 3D-printed molds and detailed instructions, allowing other programs to create their own phantoms.

“Instead of just making one model, they built a phantom-making protocol,” Stafford said. “Anyone with a 3D printer and the molding materials can replicate it.”

That approach addresses a growing need in medical education: affordable simulation. Commercial ultrasound simulators can cost thousands of dollars, limiting access.

“Budgets aren’t endless,” Stafford said. “This makes simulation more accessible.”

POCUS use continues to expand across medicine, from inpatient wards to emergency departments and rural clinics worldwide. As ultrasound devices become smaller and less expensive, scalable training tools are increasingly important.

“In many places, ultrasound is more available than CT or X-ray,” Stafford said. “Training has to keep up.”

The engineering team presented their final poster in Trent Semans Great Hall on December 8th, and the phantom is now installed in the PA school’s ultrasound lab. The students hope to share the design files widely, potentially through workshops at national meetings.

“This project highlights the incredible EGR101L engineering design course developed by Dr. Ann Saterbak, as well as a remarkable team of undergraduate engineers, and a group of Duke PA students who are dedicated to ultrasound education. It shows what’s possible when students and faculty collaborate across disciplines,” Stafford said. “It started with the PA students identifying a need—and that’s where innovation should begin.”

“This is ideal for early learners,” Stafford said. “They can see how the probe interacts with the chest and understand the anatomy in three dimensions.”

Second, the team produced reusable 3D-printed molds and detailed instructions, allowing other programs to create their own phantoms.

“Instead of just making one model, they built a phantom-making protocol,” Stafford said. “Anyone with a 3D printer can replicate it.”

That approach addresses a growing need in medical education: affordable simulation. Commercial ultrasound simulators can cost thousands of dollars, limiting access.

“Budgets aren’t endless,” Stafford said. “This makes simulation more accessible.”

POCUS use continues to expand across medicine, from inpatient wards to emergency departments and rural clinics worldwide. As ultrasound devices become smaller and less expensive, scalable training tools are increasingly important.

“In many places, ultrasound is more available than CT or X-ray,” Stafford said. “Training has to keep up.”

The engineering team will present their final poster in Trent Semans Great Hall on December 8, and plans are underway to install the phantom in the PA school’s ultrasound lab. Stafford hopes to share the design files widely, potentially through workshops at national meetings.

“This project shows what’s possible when students and faculty collaborate across disciplines,” Stafford said. “It started with students identifying a need — and that’s where innovation should begin.”