UPDATE 8/21/2017: Dr. Gurley has been named the new Chief of the Division of Nephrology at the Oregon Health Sciences University, effective January 2018.

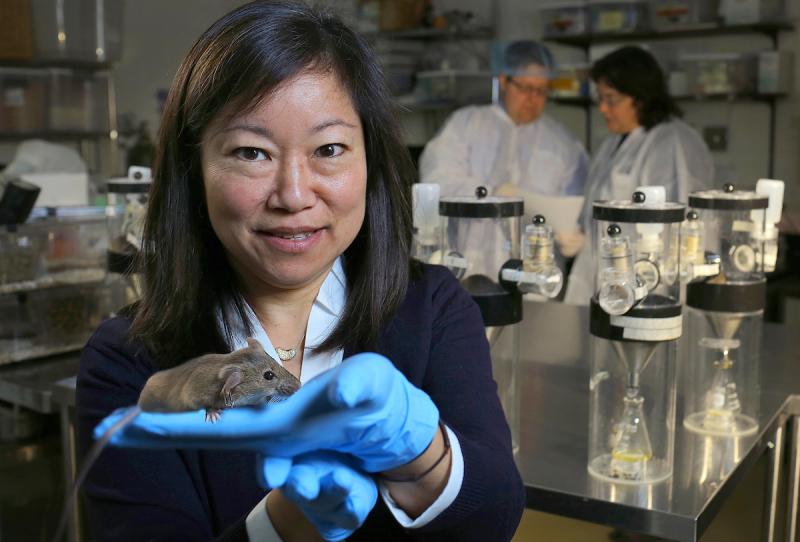

In 2016, the Duke School of Medicine selected 38 of its faculty for the new Duke Health Scholars and Duke Health Fellows Program. With funds from the Duke University Health System, the program supports the research efforts of early to mid-career clinician-scientists at Duke. Among the faculty honored are 14 individuals from the Department of Medicine, including Susan Gurley, MD, PhD, associate professor of medicine (Nephrology).

Year after year, patients with advanced kidney disease caused by diabetes bring Dr. Susan Gurley the same question: “Doctor, isn’t there something else we can do to save my kidneys?”

More often than not, Gurley has scant good news to offer. But she does make a promise: “We’re working on it.”

There is plenty of work to do. Due to the rise of Type 2 diabetes, the World Health Organization ranks diabetes mellitus a growing, global epidemic. In the United States, diabetes-related kidney disease is the most common cause of end-stage renal disease, a condition that produces not just great suffering but also swelling medical costs.

Despite that, new therapies for diabetic nephropathy have not emerged for nearly two decades, Gurley says. Better understanding more root molecular mechanisms underlying the disease’s assault on kidneys would help.

Drugs used today to treat diabetes-related kidney disease are also prescribed to patients with hypertension, lupus and other organ-damaging disorders, Gurley says. These drugs can’t always halt scarring in a patient’s kidneys.

“We’ve got to find more specific treatments,” Gurley says. “In the end it all looks the same. The kidneys scar down and can’t do their job anymore. But how it got there and what started it might be a different thing.”

Gurley intends to build a multidisciplinary research program at Duke to probe the biology of diabetic kidney disease. The project could both unearth new treatment targets and train a needed next generation of clinical scientists in this realm.

“Defining novel approaches to mitigate death and suffering due to diabetic kidney disease is one of the most important contemporary medical and public health challenges,” says Myles Wolf, MD, MMSc, chief of the Division of Nephrology.

Career starts with a love for science

The first in her family to attend college, Gurley enrolled at the University of Mississippi in the mid-1980s a smart kid from a small rural town outside Biloxi. She was interested in becoming a doctor, despite limited direct experience with medicine.

“I had no personal experience with physicians, either as a patient or as a family member,” Gurley says, but the prospect of a career that merged science with working with people appealed to her.

Science captivated Gurley so much that she remained at Mississippi until 1994 in order to earn a doctorate in chemistry. As part of lab research studies there, she probed the physical forces in play when drugs bind to DNA and this is where she realized she was absolutely committed to a career in research.

“What we were doing was valuable but it was not directly relatable to clinical medicine. That led me to realize the medical school could fill that gap,” Gurley says.

After landing a highly competitive, full-tuition scholarship, Gurley started medical training at Washington University. When she reached Duke as an intern in 1998, the faculty, medical problems and research opportunities in nephrology drew her in.

While a research fellow at Duke, Gurley joined the laboratory of Thomas Coffman, MD, to study hypertension and diabetic kidney disease. Coffman, now Dean at the Duke-National University of Singapore Medical School, was collaborating with Nobelist Oliver Smithies at UNC-Chapel Hill and others to create mouse models of diabetic nephropathy with the NIH-launched Animal Models of Diabetic Complications Consortium.

Already practiced at test tube experiments, Gurley dove into the then-emerging field of breeding genetically modified lab mice. Since then her studies on the animals have expanded understanding of angiotensin-converting-enzyme-2 in kidneys, which she has shown helps suppress hypertension. She has also identified critical roles played by AT1 angiotensin receptors in the kidney’s proximal tubule in mediating blood pressure and fluid homeostasis.

Gurley works with laboratory mice whose malfunctioning kidneys resemble human kidneys impaired by diabetes on biochemical and tissue levels. High-grade albuminuria, hypertension, and glomerulosclerosis all exist in the model she helped to create. Currently her laboratory is pursuing new evidence of genetically-regulated biological pathways within their kidneys.

“This work has great potential to provide discoveries that will have substantial translational impact,” says Coffman.

Gurley knows probing complex biology and uncovering new potential treatment approaches will take time. That does not deter her.

As chief of the renal section at the Durham VA Medical Center, she still sees patients with failing kidneys. They are still asking for more help. And she has a promise to keep.

The series of profiles of our Duke Health Scholars were written by Catherine Clabby, freelance science journalist. Photos are by Ted Richardson.