By Liz Switzer

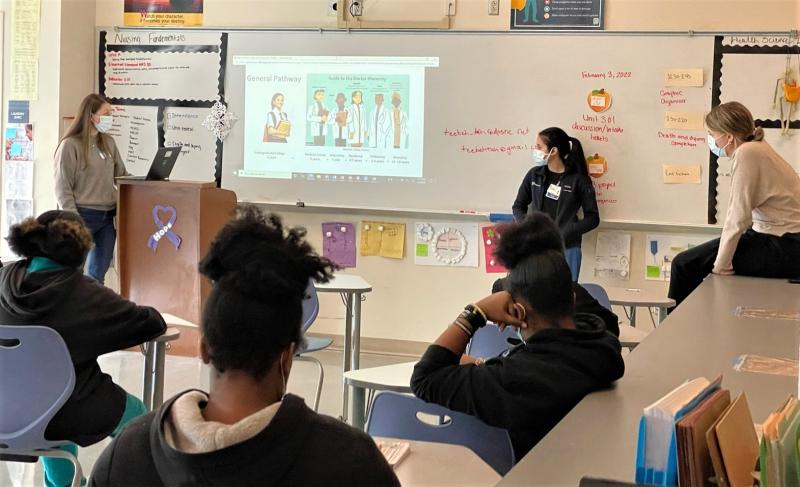

A new rotation for Internal Medicine residents at the City of Medicine Academy (CMA) in Durham encourages high school students—particularly those from historically excluded groups—to consider careers in medicine and health while giving Duke internal medicine residents a fresh opportunity to engage in greater diversity initiatives while gaining a deeper understanding of the local community.

Modeled after other pipeline student recruitment programs, the rotation was created around a Department of Medicine Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Anti-Racism (DEIAR) Committee goal to build a connection between the residency program and students in the community and foster trust between the community and the Duke Health System. The CMA, a health sciences-based magnet school near Duke Regional Hospital, proved to be a great fit for the initiative.

“The phrase ‘You can't be what you can't see,’ comes to mind a bit when thinking about some of the ways to increase representation of historically excluded groups in medicine,” says Aimee Zaas, MD, MHS, director, Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Understanding Community

So many Duke students come from other parts of the country or world so developing an understanding of the Durham community and Duke's relationship to it is a core competency of caring for patients and their families during a resident’s time at Duke, Zaas notes. “The more connection one has with the community, the better we are able to be of service as physicians in this community, understand our patients’ perspectives, and be the best provider that we can,” she adds. “It's hard to do that if you don't understand where you are.”

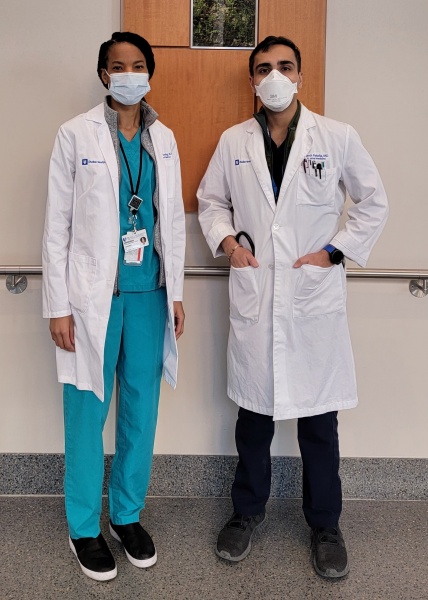

The lesson has not been lost on second year resident, Harsh Patolia, MD.

“When a patient comes to the hospital it's always numbers and a lot of medical lingo that gets thrown around, but for every patient we admit there's a story, a really important social and economic piece of the picture,” Patolia says. “As health care is evolving, you have to know more about a patient other than just their medical issues. As providers, it's our job to appreciate it, understand it and empathize with it as part of the care that we provide.”

Launched in October 2021, the program is being met with great enthusiasm, not only by the kids at CMA but by Duke residents interested in engaging in the community. So far, 20 of the 32 that signed up have been able to visit the school like Patolia and third year resident, Ceshae Harding, MD, both of whom serve as resident leads to the DEIAR Committee.

Launched in October 2021, the program is being met with great enthusiasm, not only by the kids at CMA but by Duke residents interested in engaging in the community. So far, 20 of the 32 that signed up have been able to visit the school like Patolia and third year resident, Ceshae Harding, MD, both of whom serve as resident leads to the DEIAR Committee.

“Students are not only getting exposure on how to become a doctor, but they have some mentors who look like them, who are invested in their future,” said Harding, a Jamaican native who is planning a career in academic general internal medicine. “They're getting that kind of one-on-one dedicated mentorship to make sure that this is an easier path for them, should they choose it.”

CMA teachers like Laura Tuson, a healthcare sciences instructor, are impressed with program outcomes to date. Tuson said that visits from the residents not only give her students a window into the life of a doctor, but a better understanding of the work they do and the academic training that is required.

“Many will be the first in their family to pursue higher education, so they have lots of questions about college, pre-med coursework, medical school, residency, and what comes after,” Tuson says, recalling a recent class that focused on ethical issues in health care, emphasizing that the practice of medicine is about more than just knowing the science. Another class conversation about decision-making capacity and end-of-life issues, she said, helped students see that interpersonal skills are incredibly important as doctors deal with complex situations.

Typically, twice a month three residents take the morning classes then three others take the afternoon sessions. Due to COVID-19 and regulatory hurdles, the classes started out on Zoom but later moved to in-person learning. That’s when things really took off. One popular class included the use of point-of-care ultrasound devices.

Values

The rotation is structured to be part of the regular workday – i.e. not as extracurricular activity – to reflect the value that is placed on working within the community as equivalent to other patient care and educational curriculum in the residency training program. In Tuson’s class, the curriculum is systems-based, similarly structured to the first and second years at many medical schools where pre-clinical students learn each organ system, moving from one to the next.

Residents bring lists to class of various diseases or conditions that affect each system, pertinent to the curriculum that week, and talk about these cases with the students. Discussions cover what its like to take care of a patient suffering from a particular disease, what the patient might experience, what the doctor might do to treat that person, and what might go wrong.

“We were really impressed with how sophisticated the questions were from the students,” Zaas notes.

“We were blown away,” says Harding. “So, then we asked them to help us with management and they were great at that, too. The students are always super engaged and they're able to apply what they've learned.”

Zaas is hopeful that the rotation can at some point be opened up to Department of Medicine fellows, and potentially residents from other programs. Over time, the big dream, she says is to bring the students into the hospital or clinics for direct shadowing opportunities, and open the courses to more students at the high school. Some secondary outcomes would hopefully extend to small group mentoring relationships for students who might need help with the college essay or career opportunities.

Photos: (Top) Residents Emily Romanoff, Amber Meservey and Margaret Sahu walk City of Medicine Academy students down the path of becoming a doctor. (Middle) Residents Ceshae Harding and Harsh Patolia shared their interest in academic medicine with the students. (Lower) Hannah Schwennesen, Amanda Broderick and John Barber await questions from students.